An Overview at the Overlook (Part 3: Human History)

One of the things I love about this area is that its human history is a bit of a microcosm of the history of this country.

Of course everything starts with the Native Americans, and the most recent tribe to occupy this region are the Crow. This is all ancestral Crow land, or the Apsaalooke people, and they still have a huge reservation that you can see on the north end of the Pryors. Other native American groups were here too, of course, going back many thousands of years. Within just a couple of miles from our Andersen Area there are petroglyphs in an isolated and beautiful little canyon, and a sacred medicine wheel near us in the Pryors. The Pryors are also still considered to be sacred by the Crow to this day. They have legends about mischievous ‘little people’ that live in the Pryors that will mess with your campsites if you don’t leave offerings of tobacco, for example.

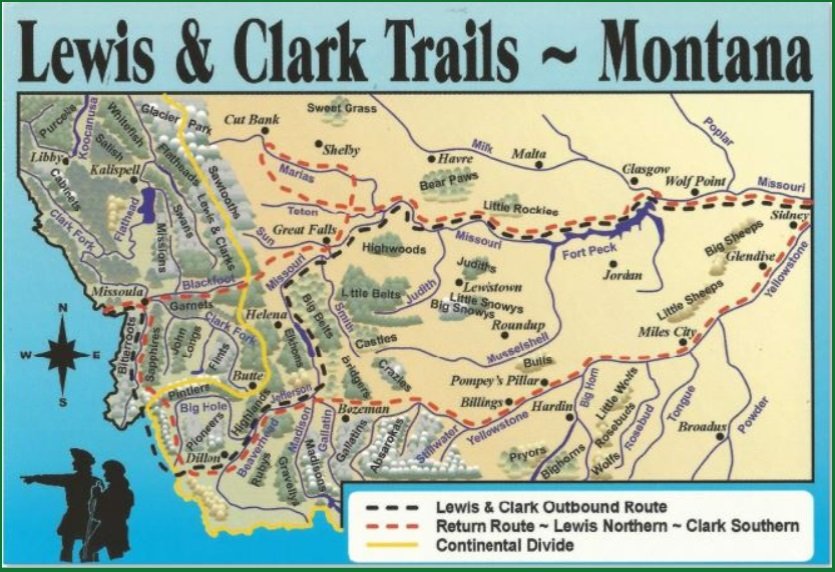

The first white men in this region were from the Lewis and Clark expedition to the Pacific in 1804-1806. They didn't pass through this exact area, but they were very close by. They traveled up the Missouri River on the way west, and then when they were on their way home they split up into two teams, with Clark leading his team on a southerly route that included the Yellowstone River, which we passed over beside that refinery. And as they went downstream, they named and mapped every river and land feature they encountered. On our way to our sites every day we’ll cross “Clark’s Fork of the Yellowstone” river. And, they were the first whites to encounter a lot of the plant and animal species out here, so many have been given Lewis or Clark’s names. “Clark’s Nutcracker” is one of the common birds out here, for example.

Shortly after Lewis & Clark’s Corp of Discovery returned East, this area became classic Mountain Man territory. Typically French, British, and American men who lived solitary lives for all but a couple of weeks during the year, trapping animals to sell their furs at big gatherings of other mountain men, Native Americans, and traders. Those gatherings, or Rendezvous, only lasted those other couple of weeks during the summers, and when they were over the men and sometimes their wives, often native women, went back into the mountains to continue trapping.

It didn’t take long for the mountains and the West to get trapped out, so the mountain men often turned to guiding military and scientific expeditions, and then to guiding immigrants to new lands in the west. Jim Bridger is one of the more famous of the mountain men who followed this path. The Bridger Mountains are named for him, as is the town of Bridger, MT, which we’ll pass by each day, as well as the Bridger Trail, which passed through the Basin, through the town of Bridger, and joined the Bozeman Trail north of here where Rock Creek meets the Clark’s Form of the Yellowstone. 1864 was the busiest year of the Bridger Trail, to give you some context.

This region certainly had a part in the Indian Wars of the late 1800s as well. Of course Little Bighorn is just an hour or so east of Billings, but even closer than that was the famous flight of the Nez Perce from the pursuing Army in 1877. Chief Joseph and his band of 800 Nez Perce men, women, and children fled and fought off the pursuing United States Army for almost 1,200 miles, while trying to reach asylum and relative safety in Canada. They made it to within 40 miles of the border before being cornered and gave up, but part of that incredible escape took place near here through the Clark’s Fork Canyon and what is now called the Chief Joseph Highway, up and through the Beartooth Mountains.

Of course you can’t talk about the Old West without talking about cowboys and outlaws. In late June 1897, the Sundance Kid (Harry Longabough) and his “Wild Bunch” gang, which included George “Kid” Curry and a few others, but predated Butch Cassidy, mostly botched an attempted bank robbery in Belle Fourche, SD, and escaped to the famous ‘Hole-In-The-Wall’ not far away on the south end of the Bighorn Mountains. When they heard a posse was coming after them there, they decided to rob the bank in Red Lodge, and must have come over this pass to get there. They came into town and scoped out the bank, but by then the telegraph wires were up and running and Red Lodge had been warned about them. (Some accounts say they were jailed in Belle Fourche, escaped, and then came to Red Lodge). The sheriff ran them out of town and chased them for 80 miles, when they were finally caught near Lavina, MT, taken to the jail in Deadwood, SD, where they promptly escaped again.

Many small towns in the West are dead or dying. There just are so few jobs. The ones that have survived to thrive are ones that were able to reinvent themselves many times over. Red Lodge was founded soon after the land was taken back away from the Crow and when coal (1866) and gold were found nearby - those two events were probably not coincidences.

Once again, everything goes back to geology, and so must we when talking about recent human history. When the Basin was flexed downward, that made a perfect place for lakes and swamps to form. Swamps surrounded by thick vegetation, and existing for millions of years, are the ingredients needed to make vast and thick layers of coal. But the term ‘coal’ is informally used to describe the carbonized remains of plant vegetation that exists in a continuum, from lignite (the dirtiest, lowest heat-content version), which is essentially like charcoal, to bituminous, to anthracite (the “cleanest”, highest btu) coal. The vast coal reserves back east, like in Pennsylvania, are ~300 million years old and have a lot of anthracite. The coal here is just ~63 million years old and is mostly lignite.

Nevertheless, the coal industry here was pretty extensive. In fact, this entire valley would have been entirely unrecognizable from what we see today. It was filled with towns, a railroad that came all the way up the valley, smoke stacks, and thousands of inhabitants, all centered around coal. The towns included Bearcreek, Washoe, New Caledonia, Chickentown, Scotch Coulee, International, and Stringtown, but only Bearcreek and Washoe exist today, and Washoe is nothing more than that tiny collection of a couple of houses.

The great American story here, though, isn’t just about mining, but of immigration from elsewhere in the world. Immigrants came from other parts of the country, but also from all over Europe where coal mining was a part of the old culture - Serbia, Montenegro, Germany, Scotland and Italy. This made all of these towns, including Red Lodge, very diverse places, with different religions, cultures, dress, and spoken languages being everyday occurrences. It also meant these places were pretty segregated - there were Italian sections of Red Lodge, Scotch, German, etc. Until fairly recently Red Lodge still celebrated their ethnic diversity by hosting a “Festival of Nations”, but that tradition died as the generations moved away from their old heritages.

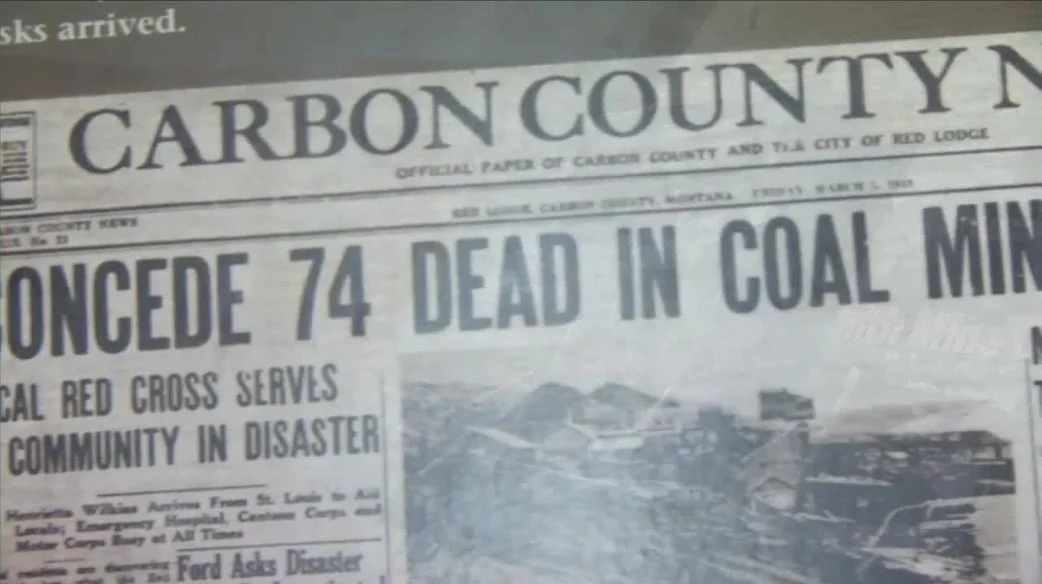

Because the coal wasn’t very good quality, and because of a drop in demand thanks to the Great Depression, the industry was on its way out when WWII came, and along with it an enormous demand for energy. That is until February 27, 1943, at 9:37am, when a massive explosion in the Smith Mine rocked one of the mine tunnels. The force of the blast knocked a 20-ton locomotive off its tracks ¼ of a mile away, but was so deep that people at the mine entrance didn’t know anything happened. More importantly, it killed 77 men and boys. The 30 who died in the blast were the lucky ones, because the rest knew they were trapped, and snow covering this Pass meant help from Red Lodge wasn't coming. Some of them wrote heartbreaking goodbye letters to their wives and mothers. Many were buried in the Bearcreek Cemetery, and many of those headstones were written in Cyrillic characters, b/c many of those immigrants had not yet learned English. That was, for all intents and purposes, the end of coal mining in this region, though it survived in drips and drabs for a few more decades.

Let’s back up quickly to the Great Depression. This region was hit hard by the Depression, but it only made a bad situation worse. Montana historians will tell you the Depression arrived in Montana ten years before the rest of the country. But like everywhere else, the situation slowly improved with New Deal era programs, like the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration. The irrigation ditches you’ll see along the roads throughout the region make much of the agriculture in the area possible. Trails and campgrounds along the Beartooth Highway were built with New Deal Era money and jobs, as were several dams that provide water and electricity to people around here.

Now, as I said, towns out here don’t really survive for the most part without reinventing themselves, and Red Lodge has certainly done that. It is also lucky - geographically lucky. Connecting Red Lodge to the northeast corner of Yellowstone is the Beartooth Highway - what some have called “the most beautiful drive in America”, and a true marvel of engineering. The Beartooth Front is also home to some snow skiing trails, giving Red Lodge a year-round tourist industry.